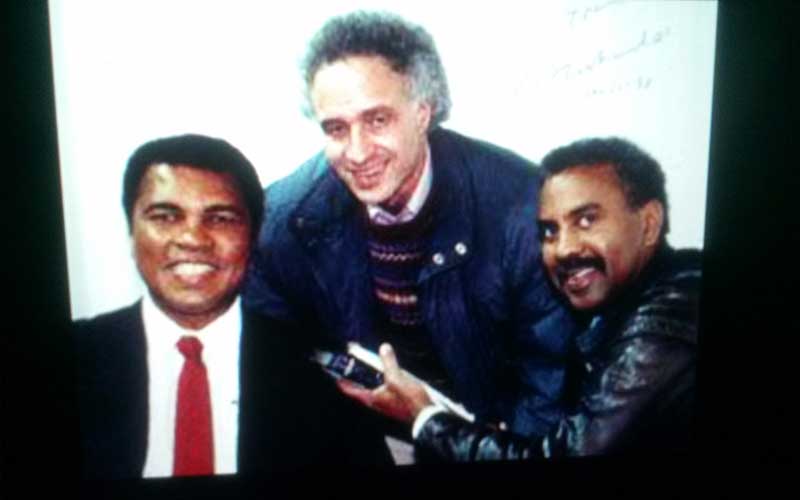

From Michael Jordan to Muhammad Ali, Ernie Banks, Walter Payton, Tiger Woods, Dick Butkus and George Halas, I have interviewed many of the biggest names in sports

I have written newspaper articles on deadline from inside a cramped toll way phone booth during the middle of a snowstorm. Relentlessly, I have pounded out artful prose from the driver’s seat of my car, from the middle seat in row 25 of an overseas United Airlines flight, from the dank bowels of a sweaty gym and, of course most frequently, from the overbearing writing quarters of a stadium press box.

During my 41-year career as a sportswriter and columnist with the Chicago Tribune, I learned to adapt and focus on the writing process and not the sometimes-uncomfortable venues that beckon. Whether the dateline read: Sydney, Australia or Mesa, Arizona, my job was to tell the stories in the most compelling, accurate and yet succinct manner in order to capture readers’ attention and provide insightful information.

Writing remains a work-in-progress for all of us. Yet the more you write, the easier and more comfortable it becomes. As a journalist, I found that I was able to focus more on the reporting and interviewing process as the years went by because the actual writing routine became second nature.

Whether I was interviewing Michael Jordan, Walter Payton, Pete Rose, Mike Ditka, Tiger Woods, Ernie Banks or Muhammad Ali, I realized that above all they were ordinary human beings first who just happened to possess extraordinary athletic skills. And it was up to me also to reveal their vulnerability, their insecurities, their human-interest side for the readers.

Once I conducted the interviews, researched the facts, made the right phone calls and prioritized the information, the stories pretty much flowed as if I were simply telling a huge audience or a buddy at the bar about a particular game, incident or encounter. You never want to bury the lead. Tell the most important facts first while sprinkling in illustrative anecdotes and additional pertinent information.

In addition to becoming a columnist, I had the privilege of covering the 2000 Summer Olympics, dozens of Super Bowls, World Series and NBA Finals, as well as a couple of Stanley Cup Finals and college football bowl games for the Chicago Tribune.

As a beat reporter, I traveled daily with the Bulls, Cubs and Bears before covering local college teams at Northwestern, Northern Illinois, Loyola and De Paul. I have enough old media credentials to decorate several Christmas trees. And I have enough hotel points to be listed as a Lifetime Diamond member. They are tangible reminders of how far I came from my days writing for the Wittenberg Torch in the 1960s.

Because sports writing involves the recounting of so many unscripted live events, the drama and suspense created lend themselves to captivating edge-of-your-seat accounts. I learned early on that many sports stories write themselves, in a manner of speaking, if we allow the proper sequence of events to unfold for the reader. It is at that point that we writers should try to put ourselves in the minds of the reader to fill in the blanks.

What questions might they have at this point?

How did the centerfielder feel after he dropped the fly ball?

What was going through the mind of the quarterback after throwing the game-winning touchdown pass?

I received some of the most enlightening, heart-felt answers after asking some of the most basic questions. Capturing raw emotion or general human vulnerability often depends on simply artfully asking the right questions, and then the right follow-up question. And one of the most underrated skills of an effective reporter and writer is being a good, compassionate listener as you draw out that emotion.

There have been times when I was in the middle of writing a powerful human-interest story that I became choked up and had to pause. Those were the types of stories that I hoped would provoke similar reaction from readers.

One such column was about former Chicago Bears lineman Revie Sorey, who had suffered a stroke on March 25, 2012, that left him unable to speak. I visited Sorey, also a longtime personal friend, at a rehabilitation center in Chicago. I wrote that we sat in “comfortable silence for about an hour.”

An important responsibility for a conscientious writer is simply to observe and describe details of the surroundings. Another heartfelt column evolved from my long phone conversation with former Bears quarterback Erik Kramer, who had lost his 18-year-old son, Griffen, to a heroin overdose on Oct. 30, 2011. A distraughtKramer tried to commit suicide on Aug. 19, 2015, yet somehow managed to survive a gunshot wound to his head.

One of my great challenges as a newspaper man was re- adjusting my style when I wrote 11 books over my career. As a newspaper reporter, we are urged to be very economical with our words. Get to the point and omit extraneous information. Space in newspapers, especially over the past couple of decades, is precious.

But some of my books were 70,000 or more words at the publisher’s request. That meant that topics that perhaps would be 600 words in a newspaper article would be 6,000 words or more for a chapter in a book. I had to learn to expand on my thoughts as an author.

When I began at the Chicago Tribune in 1974, typewriters were still in use, and the internet was unimaginable. Over time, I witnessed the evolution of devices from clunky computers that resembled sewing machines to more sleek equipment that make writing from remote locations more accessible. I was a proud pioneer in our sports department when it came to video-taping interviews on cellphones and flip-cams about 10 years ago. Now all reporters are pretty much required to do so. They called me “Mr. Gadget” because of all the recording devices I packed inside my sport coat and back pockets.

My theory is that anything that can help provide more accurate, illustrative information for the reading audience the better.

I tell young students today that it is impossible to imagine what media platforms might be prevalent 30 or 40 years from now, just as it was unfathomable when I first started in this profession. But what is clear is that there always will be a need for prolific writers who can accurately and effectively chronicle the events of the day.

(This story originally appeared in the Wittenberg Magazine)